We have just made a submission to the Senate Select Committee on PFAS. Submissions closing date: 19 December 2024.

PFAS is short for Per and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances. It is a chemical class covering over 14,000 chemicals, in which only a small proportion have had their toxicity assessed. The chemicals are man-made and do not exist naturally. They are bio-persistent and bio-accumulative, and so are called Forever Chemicals, because they do not breakdown but persist in the environment.

New to the PFAS scandal? Start with this 48 minute documentary : The Forever Chemical Scandal | Bloomberg Investigates made in 2023.

We accidentally became aware of the issue of PFAS forever chemicals and synthetic turf in the last few years. While not a core climate issue, the growing presence of PFAS in the environment, to the extent that it now exceeds a planetary boundary, should concern us all.

While being aware of the many sources of PFAS now in the environment we chose to focus our submission on the neglected area of PFAS and Synthetic turf.

Executive Summary

Our interest in PFAS started with a campaign in 2020-2021 to stop a grass multi-use sports field in Coburg North in Melbourne’s northern suburbs being converted to a synthetic turf sports pitch. This was one of eight Council synthetic turf projects in a pipeline of projects.

We continued to investigate the scientific literature on artificial turf and discovered that PFAS chemicals are routinely used in the manufacturing of turf fibres and matting as a lubricant to prevent the extrusion machines from clogging up. PFAS may also be added to plastic grass strands for UV protection and to prevent them from breaking.

- Synthetic Turf is both manufactured here in Australia and also imported for sale.

- PFAS can leach from artificial turf into local water supplies, and aquatic ecosystems.

- PFAS chemicals are not manufactured in Australia but imported subject to Federal Government regulation.

- There appears to be no chemical testing of synthetic turf products in Australia.

- There appears to be no regulation of chemicals in synthetic turf products in Australia.

- NSW EPA and Victorian EPA have declined to test synthetic turf chemical content, despite evidence from USA and Europe, and being asked to do so.

- Synthetic turf is not listed by the PFAS Taskforce as a potential source for PFAS in the Environment.

- Synthetic turf as it wears and breaks down produces microplastics pollution which is both airborne and waterborne. Any Fluoropolymers/PFAS in synthetic turf will combine with microplastics pollution increasing its environmental and health impact.

Synthetic turf at end of life: Recycling synthetic turf with unknown chemical content risks furthering toxic contamination in the down-cycled products produced; or risks toxic leaching if disposed of in landfill; or causes PFAS in bottom ash and as airborne pollution if put through an industrial waste Incinerator.

Both microplastics and PFAS affect environmental ecosystems and human health, and when combined together, or with other toxic pollutants, may have both an additive and synergistic impact.

PFAS in the environment now has many sources. Scientists have tested and found PFAS chemicals widely on the earth and concluded that rainwater globally is contaminated often above all drinking water standards. Because of biopersistence, these chemicals are likely to continue to cycle in the hydrosphere.

Global soils are now ubiquitously contaminated. Contamination is poorly reversible.

Planetary boundary for chemical pollution now being exceeded. Scientists recommend that “to avoid further escalation of the problem of large-scale and long-term environmental and human exposure to PFAS, rapidly restricting uses of PFAS wherever possible.”

Conclusion and Recommendations

We are aware of the many sources of PFAS pollution including from clothes, carpets, cosmetics, consumer products, in our water supply, and in takeaway food packaging.

Our submission has focussed on a niche use of PFAS chemicals, as part of artificial turf. This use has been substantially ignored by official agencies regulating PFAS chemicals.

We found wide use of artificial turf with poor regulation of its chemical content deeply concerning. PFAS is just one toxic aspect of this product that has multiple problems and we judge as a climate maladaptation.

General Recommendations:

- PFAS chemicals should be regulated and addressed as a class

- Use of PFAS in manufacturing in Australia should be tightly regulated, controlled and phased out.

- During PFAS phase out all products using PFAS implement full product tracing.

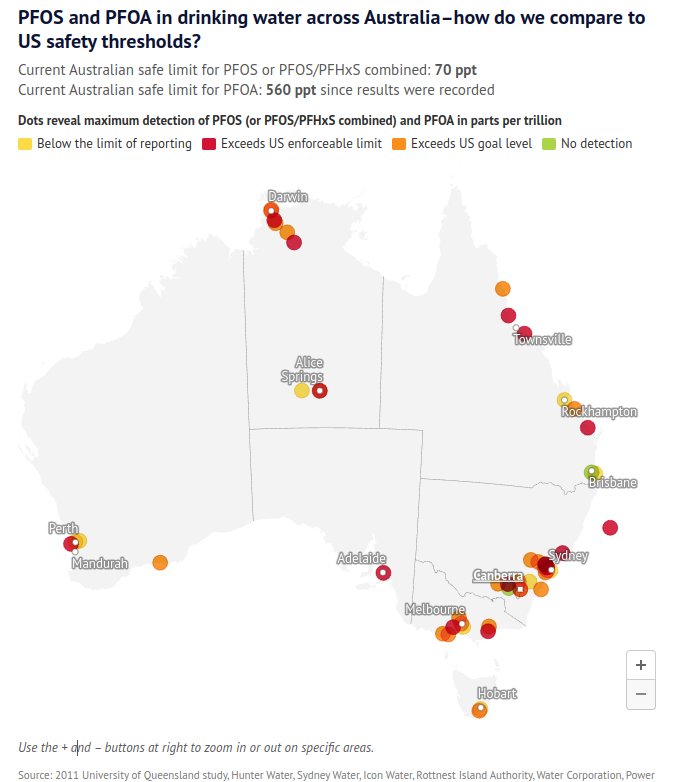

- Update Australian drinking water guidelines to reflect the US EPA standards and finding that there may be “no safe level of PFAS exposure.”

- Given PFAS contamination is now part of the hydrosphere, improve water treatment to ensure best available technology (BAT) to limit PFAS contamination as close as possible to zero

- Address wastewater treatment plants PFAS contamination of biosolids and their use for agriculture.

- We have had a voluntary phaseout of PFAS in food packaging. We should now move to mandatory removal of PFAS from all food contact packaging

- Fluorinated Refrigerants. Rapidly replace refrigerants with non-fluorinated options and raise this in international fora.

- The Australian government should ratify the three chemicals PFOS, PFOA and PFHxS for inclusion in the listing on the Stockholm Convention on Persistent Organic Pollutants 2001. Australia should also support the proposed global ban on perfluorocarboxylic acids (PFCAs) as recommended by the Persistent Organic Pollutants Review Committee (POPRC)

Specific Recommendations for Artificial Turf:

- Manufacturers should be compelled to disclose full chemical makeup of the product.

- The chemical composition of Artificial turf should be tested.

- Import of Artificial turf should be banned.

- Use of Artificial Turf should be restricted to certified PFAS free products.

- Given the global plastics pollution crisis and with a Global Plastics Treaty presently under negotiation, artificial turf is a non-essential use of plastics that contributes to greenhouse gas emissions, microplastics pollution and adds to urban heat. Stringent triple bottom line governance arrangements are needed to justify any artificial turf use, including implementing microplastic pollution mitigation measures.

Submission

Background Reading

This is additional information on PFAS we have gathered, most of which we did not include in our submission, but all of which is relevant.

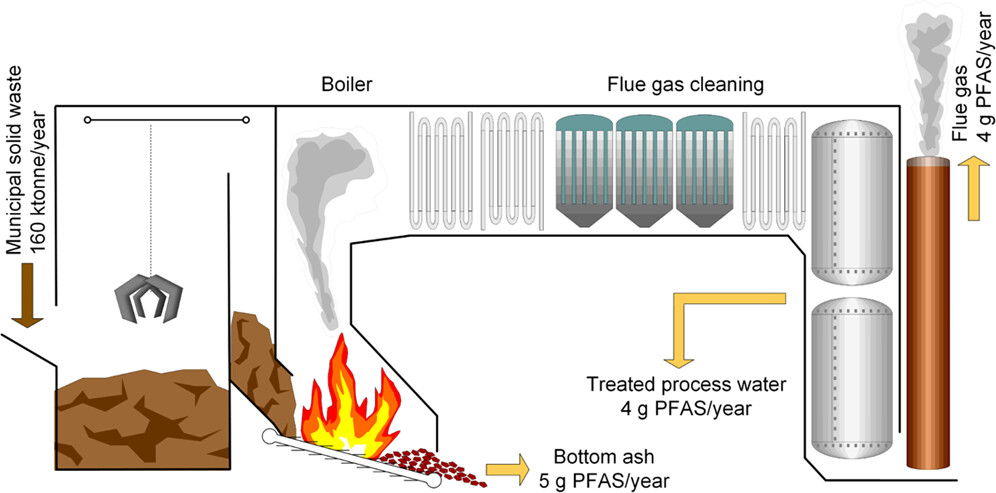

Waste to Energy Incinerator Plants are a source of PFAS in the Environment:

We note Cleanaway has a development licence going through EPA assessment process for a Waste to Energy Incinerator at Wollert. If this project is approved, almost certainly local residents will be exposed to PFAS in air pollution. See our Submission on this project, especially Paragraph 4 for just one PFAS chemical tested at a Netherlands Waste Incinerator plant that was found to be polluting surrounding residents.

From: Björklund S, Weidemann E, Jansson S. Emission of Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances from a Waste-to-Energy Plant─Occurrence in Ashes, Treated Process Water, and First Observation in Flue Gas. Environ Sci Technol. 2023 Jul 11;57(27):10089-10095. doi: 10.1021/acs.est.2c08960. Epub 2023 Jun 15. PMID: 37319344; PMCID: PMC10339719.

https://pubs.acs.org/doi/full/10.1021/acs.est.2c08960

PFAS in Drinking water in Australia

From the Age, ‘There’s no safe level’: Carcinogens found in tap water across Australia, Carrie Fellner, June 11, 2024 https://www.theage.com.au/national/there-s-no-safe-level-carcinogens-found-in-tap-water-across-australia-20240606-p5jjq3.html

Avoiding PFAS from your diet? Very difficult but there are some things you can do

This article advises how to minimise PFAS ‘forever chemical’ exposure in your diet. It insinuates don’t live near a military base where PFAS chemicals were used in fire-fighting foams, or eat seafoods produced nearby. But it does not highlight living in the immediate surrounding area or down-wind from a Waste Incinerator or playing on artificial turf. Oh, Cleanaway are proposing a Waste Incinerator for Wollert and with northerly winds much of the northern suburbs of Melbourne are downwind of the proposed Incinerator.

Yes, we have allowed companies to pollute primary food systems and packaging so avoiding PFAS chemicals is impossible, we can only adopt minimisation strategies.

https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/article/2024/jul/22/pfas-forever-chemicals-diet

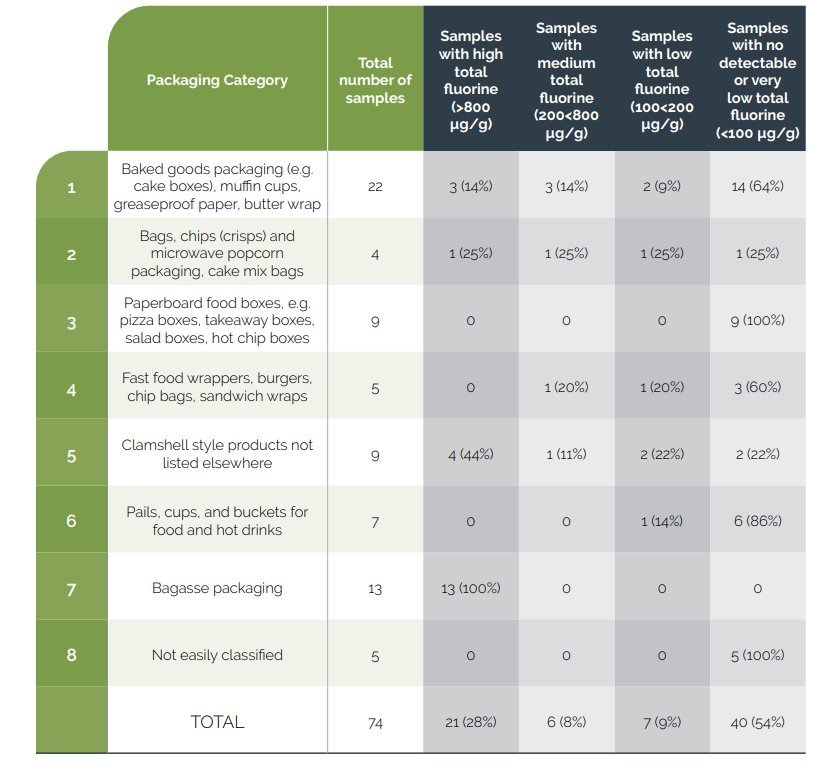

PFAS in Food Packaging

PFAS class of chemicals and use in food packaging in Australia. The Federal Government adopted a voluntary phaseout of PFAS in packaging, but this should have been a mandatory process.

In February 2022 the Australian Packaging Covenant Organisation (APCO) published a Study – PFAS in Fibre Based Packaging.

A few comments first before quoting from the executive summary:

1. The prevalence of PFAS chemicals in fibre food packaging. Over a quarter of the 74 samples contained high levels of PFAS (above 800 ppm). All 13 of the bargasse packaging (those clamshell boxes for takeaways) had high flourine signatures. Only about a quarter of the samples tested had no detectable PFAS. Australia may be better than the US with regards to prevalence of PFAS in food packaging, but this study shows we still have a very concerning problem.

2. The study was not set up to analyse migration of PFAS in packaging to food consumed. So a known unknown about human exposure.

3. The 28 common PFAS chemicals were not found in most of the samples that detected PFAS. So manufacturers are using PFAS chemicals with little information on toxicity which poses a risk to health.

4. The emphasis is on self-regulation with packaging companies urged to phase out PFAS in their packaging, providing no timeline or guarantee of human safety.

5. PFAS in fibre based packaging when recycled contributes to increasing background levels of PFAS accentuating the problem. Whether containers with PFAS are either recycled or go to landfill they are enhancing the environmental problem due to persistence of PFAS in the environment.

6. Since 2002, the Australian Government National Industrial Chemicals Notification and Assessment Scheme (NICNAS) has published a number of alerts on PFAS. NICNAS has recommended that Use of PFOS-based and related PFAS-based chemicals should be restricted to essential uses, for which no suitable and less hazardous alternatives are available. I ask, Is self-regulation sufficient for a hazardous substance used in food packaging? See National position statement here: https://federation.gov.au/sites/default/files/about/agreements/appd-national-pfas-position-statement.pdf

From the executive summary of the APCO study:

“This study piloted a scientific methodology to identify the presence and type of PFAS in a range of fibre-based, food contact packaging, and understand potential implications for recycled content in packaging and compostable packaging. A total of 74 confidential packaging samples were provided by nine APCO Member companies for analysis.

“Scientific testing of the samples was performed in two phases. First, all 74 samples were screened using a high-throughput method for ‘total fluorine’, which is an indicator of PFAS. In the second phase, a subset of 35 samples were then tested to see whether they contained 28 specific members of the PFAS family. These 28 PFAS are readily identifiable through established scientific testing.

“The Phase 1 results indicated that just over a quarter of the samples contained high levels of PFAS (above 800 ppm). The samples with high total fluorine were concentrated in the ‘bagasse’ category of packaging products. Other packaging types had variable levels of PFAS. Roughly a quarter of the samples tested had no detectable PFAS.

“When the samples with high total fluorine were tested for 28 specific PFAS in Phase 2, these 28 PFAS did not appear in most cases. This indicates that other members of the PFAS family are responsible for the Phase 1 results. A TOPA analysis confirmed the likely presence of unknown PFAS ‘precursors’ and other ‘polymeric’ PFAS.

“While the identity of these unknown PFAS cannot be easily determined, unidentified PFAS should be treated in the same way as known PFAS and steps taken to transition them out of packaging.

“This study did not consider the migration of PFAS into food, but instead focused on understanding the relevance of PFAS in packaging in the context of a circular economy. Food Standards Australia New Zealand (FSANZ) has undertaken several surveys of PFAS in the Australian food supply including packaged foods. The most recent of these, the 27th Australian Total Diet Study (2021) looked at PFAS levels in a broad range of Australian foods and beverages. The study found that PFAS levels in the general Australian food supply are very low and there are no food safety concerns. An overview of FSANZ’s work on PFAS can be found on the FSANZ website.

“In the context of a circular economy, PFAS in fibrebased recyclable or compostable packaging have the potential to contaminate recovery systems over time. If composted, most of these chemicals will not break down, and those that do will form other PFAS.

“If recycled, these chemicals may transfer to recycled products – though this has not yet been confirmed in Australia. To avoid these problems, APCO is working with industry to deliver a phase-out of PFAS in fibrebased, food contact packaging – consistent with the objectives of the National PFAS Position Statement.”

The big problem with PFAS in takeaway food packaging is small businesses are unaware of the issue when purchasing the packaging product, as are consumers.

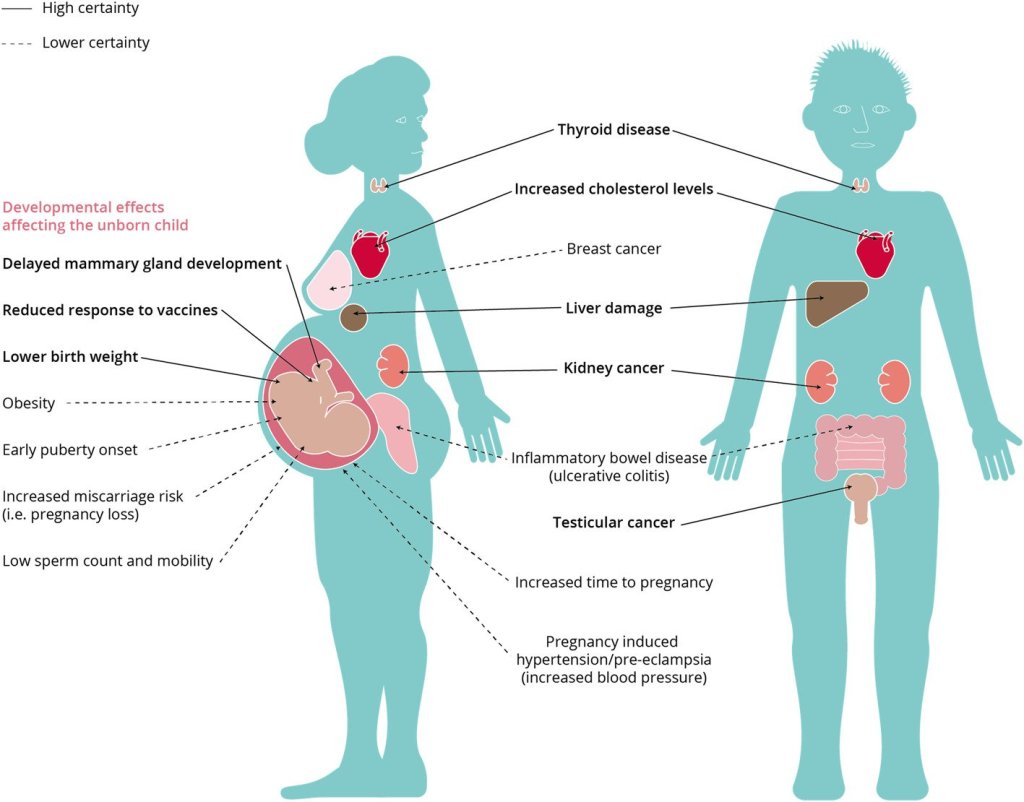

So what are the PFAS human health effects?

PFAS chemicals are bioaccumulators, so they accumulate over time. This is a large class of chemicals and the human impacts have only been determined for a small subset of chemicals in this class. Many of these chemicals are being used with poor information on toxicity.

This October 2020 study provides a reasonably current review of the science on health effects of PFAS chemicals: Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substance Toxicity and Human Health Review: Current State of Knowledge and Strategies for Informing Future Research.

https://setac.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1002/etc.4890

“Epidemiological studies have revealed associations between exposure to specific PFAS and a variety of health effects, including altered immune and thyroid function, liver disease, lipid and insulin dysregulation, kidney disease, adverse reproductive and developmental outcomes, and cancer. “

Australian Department of Health have information on health impacts of PFAS here: https://www.health.gov.au/topics/environmental-health/about/environmental-toxins-and-contaminants/pfas#potential-effects-of-pfas-exposure

PFAS and Microplastics

As artificial turf produces microplastics as it wears, and is also known from US and European scientific testing to contain PFAS chemicals, we should understand the environmental and health impacts when combined.

Very recent research which we feature in our submission has highlighted that PFAS and Microplastic particles when combined may add to developmental failures, delayed maturation, and reduced growth in aquatic species. Historical pollution exposure lowers tolerance to chemical mixtures. The combined effect of the persistent chemicals analyses was 59% additive and 41% synergistic.

As microplastics are now found in all areas of the human body, the combination of PFAS and microplastics poses a human health threat beyond just considering the impact of each.

Read more at The Guardian: PFAS and microplastics become more toxic when combined, research shows (26 Nov 2024)

The Australian Science Media Centre recently featured the widespread nature of microplastics in humans.

Plastics, once considered a ‘wonder material’, have started to look a lot less fantastic in recent years. Microplastic pollution is by no means a 2024 phenomenon, but this year researchers found the tiny plastic specks in human brains, penises, testicles, placentas, urinary tracts and arteries. How these plastic fragments are affecting our health remains unclear, but the study on human arteries, released in March, found people whose blood vessels contained microplastics were 4.5 times as likely to have a heart attack or stroke, or to die, than those without them.

We need to consider not only the health impact of micoplastics and PFAS singly but their combined synergistic impact on aquatic ecosystems and on human health.

Natural Turf Alliance

The Natural Turf Alliance, which Climate Action Merribek is a member of, put out this email update on 3 December 2024 on PFAS and Microplastics – Key Insights and Reports.

1. Health Risks of PFAS and Synthetic Turf

The Natural Turf Alliance has prepared a detailed report examining the health risks posed by PFAS in synthetic turf, including results from recent local PFAS testing.

Access the NTA Report

2. UTS Final Report on the Chemical Composition of Synthetic Turf (2022)

This comprehensive study by the University of Technology Sydney provides valuable data on the chemical composition of synthetic turf and its implications.

Read the UTS Report

3. PFAS and Microplastics: A Growing Toxic Threat

An investigative report from The Guardian sheds light on the toxic risks posed by PFAS and microplastics in synthetic fields and broader environments.

Read the Article from The Guardian

4. Whistleblower Advocacy for Scientific Integrity

This insightful piece explores the journey of Dr Kyla Bennett, a US based whistleblower advocating for scientific integrity in reporting PFAS and microplastics’ environmental effects.

Read the Medium Article

5. PFAS in the Environment: PFOA More Widespread Than Expected

A new report reveals how PFAS chemicals, particularly PFOA, transform in the environment, leading to its presence being more widespread than previously understood. The study underscores the urgent need for improved environmental monitoring and action to address this growing issue.

Read the Article from ABC News (29 Nov 2024): Prevalence of PFAS ‘forever chemical’ in the environment likely significantly underestimated: study

Join the Conversation

These findings highlight the urgent need to promote safer, natural alternatives to synthetic turf and engage in policy discussions. We encourage all members to share these resources with their networks and contribute to our advocacy efforts.