The Department of Infrastructure and Transport is conducting a preliminary survey to inform a Transport and Infrastructure Net Zero Roadmap and Action Plan. The survey closes 22 December 2023.

Australia’s transport sector is the third largest source of Australia’s greenhouse gas emissions, amounting to 19%. Since 2005, transport sector greenhouse gas emissions have increased by 11% and are currently projected to be the largest in Australia by 2030.

The following submission was made to the set survey questions. The video and photos were not included in the submission. The video on Paris bike lanes well illustrates Paris as a rapid urban transformation.

7.What are the key opportunities for decarbonising transport and transport infrastructure?

- Moving long distance freight from road back to rail

- Boosting active transport infrastructure for urban areas, national e-bike subsidy

- Fuel efficiency standards, at least as ambitious as Europe, if not greater to drive EV uptake

- Ammonia fuel for shipping from green hydrogen electrolyzers, battery electric for short distance ferries.

- Capping aviation demand by limiting airport expansion, increasing aviation fuel exercise on par with ground transport, Sustainable Aviation Fuels, Battery electric for short haul (regional) flights as it becomes available. Prohibition on short haul flights unless battery electric.

* 8. What are the key barriers for decarbonising transport and transport infrastructure?

1. Lack of substantial investment in rail network. Long range freight has been steadily moving to road as interstate roads have been upgraded. There needs to be investment to upgrade the rail network to increase its speed and efficiency. We are not talking about High Speed rail, but some key upgrades could reduce intercapital rail times for freight and passenger service. This might also provide an alternative to some aviation travel. See Philip Laird, The Conversation, 19 December 2023, Australia’s freight used to go by train, not truck. Here’s how we can bring back rail – and cut emissions, https://theconversation.com/australias-freight-used-to-go-by-train-not-truck-heres-how-we-can-bring-back-rail-and-cut-emissions-219332

2. Concentration on roads and EV funding, not looking more holistically at moving people not cars. We note the absence of any national e-bike subsidy program to accompany the EV subsidy. A national e-bike subsidy would encourage modal shift, especially in urban areas. Families could invest in an e-bike instead of a second car to do school drop-offs and pickups, and short shopping trips. See We Ride, Nov 2021, E-Bike Subsidy for Australians, https://www.weride.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2022/04/WeRide_e-Bike_Subsidy_Report_FINAL-lores.pdf

Federal government needs to cooperate with State government and Councils regarding Sustainable Transport planning and active transport infrastructure.

The IPCC has identified that modal shift to active transport contributes to reduction in transport emissions and also provides health and environmental co-benefits. One of the IPCC sixth assessment authors, a co-chair of Working Group I, Dr Valérie Masson-Delmotte, collated all the information in the 3 working group reports (2021-2022) on the importance of transport mode shift and cycling as a solution to climate change. https://threadreaderapp.com/thread/1527679061165752322.html

This also reduces resources used in cars and tackles congestion issues. Note: Muhammad Rizwan Azhar, Waqas Uzair, The Conversation, 17 November 2023, The world’s 280 million electric bikes and mopeds are cutting demand for oil far more than electric cars, https://theconversation.com/the-worlds-280-million-electric-bikes-and-mopeds-are-cutting-demand-for-oil-far-more-than-electric-cars-213870

A recent Melbourne study published in March 2022 (Pearson et al) highlighted that there is a huge number of people who own a bike and are interested but concerned with cycling. The lack of dedicated cycling infrastructure deters these people from being active cyclists. There is also a gender bias in this. It highlights the need for local councils and State Government to invest in separated cycling infrastructure which will bring multiple benefits in more people cycling, and reducing congestion, reducing transport emissions. The researchers concluded: “Our results show the potential for substantial increases in cycling participation, but only when high-quality cycling infrastructure is provided.” Pearson et al (March 2022), The potential for bike riding across entire cities: Quantifying spatial variation in interest in bike riding, Journal of Transport & Health, Volume 24, March 2022, 101290, https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2214140521003200

The Victorian State Government in a Climate Transport Pledge (2021) has set an active transport 2030 pledge target of 25 per cent share of all trips in Melbourne. But in State transport budgets active transport gets less than 0.5 percent of the state transport budget. It is not on track to meet its own pledge. Cutting Victoria’s emissions 2021–2025 Transport sector emissions reduction pledge, May 2021. https://www.climatechange.vic.gov.au/victorian-government-action-on-climate-change/Transport-sector-pledge-accessible.pdf

3. EVs: price and charging infrastructure are key obstacles. The EV Subsidy helps address the first. Having Corporate and Government fleets adopt EV purchases will flow through to an EV second hand market to make these vehicles more affordable. Business Tax writeoffs for new petrol/diesel vehicles should be ended, but continued for EV utes, vans. Charging infrastructure needs to be further rolled out around Australia to dispel range anxiety.

4. Shipping emissions. Port regulations may require upgrading to enable ammonia as a ship fuel. Shipping fleets will need to upgrade engines. Both green ammonia as a fuel for major shipping and battery electric for harbour vessels. Incentives and disincentives may need to be put in place to encourage transition by ship owners. Andrew Forrest has done an initial conversion of ons supply ship which he sailed to Dubai, but was forced to use the diesel engines as the port regulations were not able to encompass using ammonia. Forrest has expressed that we wants to convert the whole Fortescue fleet to being green ammonia powered. This transition should be facilitated by the Federal Government as a corporate leading action, to encourage other ship owners to step up.

5. Aviation has received substantial infrastructure subsidies over past decades in airports and roads, but also in fuel tax excise. Aviation is very difficult to decarbonise. While ground side infrastructure operations can have their carbon impact reduced through dedicated solar farms for energy, improved electrification of operations, waste reduction, most of the carbon emissions are on the airside. The climate impact of aviation comes partly from the CO2 emissions, particulates and nitrous oxides pollution, and high altitude climate impacts (which are often estimated at 2 or 3 times as much as the CO2 pollution)

Sustainable Aviation Fuels, Battery electric for short haul (regional) flights as it becomes available are only partial solutions. Prohibition on short haul flights unless battery electric is possible. Controlling aviation demand by stopping airport expansion is one option. Imposing a frequent flyer levy is another option.

Andrew Macintosh and Lailey Wallace (ANU Centre for Climate Law and Policy) in the study “International aviation emissions to 2025: Can emissions be stabilised without restricting demand?” concluded that “Stabilising international aviation emissions at levels consistent with risk averse climate targets without restricting demand will be extremely difficult.” Macintosh and Wallace (2009), International aviation emissions to 2025: Can emissions be stabilised without restricting demand? Energy Policy Volume 37, Issue 1, January 2009, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enpol.2008.08.029

While short haul flights are often cited as causing most CO2 emissions, there is also a technology-driven trade-off between the reduction of NOx and CO2 emissions in jet engines. All flights need to be assessed both for their CO2 and non-CO2 emissions, and the climate impact of these emissions at various cruising altitudes. For Long haul flights “time flown on cruise level is an important factor for the climate effect of each flight. The main reason for this is that NOx being emitted on high altitudes (i. e. cruise levels) has an increased climate impact (Lee et al. (2010) and Lee et al. (2009)).” argues Janina Scheelhaase, in a 2019 research paper. Scheelhaase, Janina D., 2019. “How to regulate aviation’s full climate impact as intended by the EU council from 2020 onwards,” Journal of Air Transport Management, Elsevier, vol. 75(C), pages 68-74. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S096969971830334X

9. How can the Australian and state and territory governments address these challenges and enable opportunities?

On road transport, public transport, active transport there needs to be a national sustainable transport plan with buy in by all State Governments. This needs to address:

- How to move road freight back to using rail, perhaps with using efficient intermodal interchanges.

- Encouraging urban modal shift to active transport and public transport including funding in state transport budgets and Federal grants.

10. How can industry address these challenges and enable opportunities?

Industry and Corporations need to rapidly upgrade vehicle fleet to EVs.

Be prepared to support rail freight as an option.

Reduce corporate flying, use more video conferencing

11. How can individuals address these challenges and enable opportunities?

Particularly for urban areas: Use more public transport, walking and cycling into everyday activities. This also has health co-benefits, and reduces congestion, particle pollution.

For rural and regional areas, upgrade to EVs

Avoid flying as much as possible.

12. Can you provide examples that you’ve seen of successful actions taken by governments in Australia or overseas to support transport and transport infrastructure decarbonisation? Why are they effective?

Reduced short haul aviation: In May 2021, France positioned itself as the frontrunner in a carbon-cutting train renaissance when its government enacted a ban on domestic flights where the journey could be done by train in less than two and a half hours.

European countries like Denmark, the Netherlands, and Germany are leading in creating safe, convenient, and accessible cycling conditions with bike networks that extend throughout cities and across their entire countries. Cities like Paris (a top-50 emitting city) have set bold aspirations to construct safe biking infrastructure that provides access by bicycle to all areas of the city and have also reduced the number of on-street parking spaces and lanes available to car travel, as well as the posted speed limit (City of Paris 2021; Pucher and Buehler 2008), Paris now has more than 150 kilometers of bike lanes, with 52 of these added since the pandemic; among other measures, this has helped lead to a 60 percent reduction in car trips within the city between 2011 and 2018 (Atelier Parisien d’Urbanisme 2021). Another important development making cycling more accessible to many is the growing availability of affordable electric bikes.

13. Do you have any other comments?

Transport sector is difficult to decarbonise, and needs to be addressed in discrete sectors.

Aviation will be the most difficult to decarbonise and may need restrictions on demand while technological breakthroughs and innovation happens with electric powered flight, use of hydrogen, hybrid technologies, sustainable aviation fuels and green electro-fuels. Long Haul aviation may prove particularly difficult.

Shipping emissions will entail moving to alternate fuels. Green Ammonia seems to be a likely alternative for major shipping, while battery electric may be suitable for harbour operations and ferries.

We have allowed dependency to grow on long haul road freight. We need to reverse this by investing in upgrading the interstate rail network to make it more efficient. This may entail replacing sections of track, signalling and antiquated rail infrastructure. This could reduce rail freight times and passenger times. Intermodal transfer stations would assist in road end delivery in an efficient manner. Moving more freight by rail would substantially reduce transport emissions.

Diesel trains are more efficient in moving freight than the equivalent weight being moved by diesel trucks. Trains can also be upgraded to battery electric or ammonia powered. We should be watching innovations in the mining sector for being applied to reduce rail emissions more generally. This also has co-benefits in addressing the road safety issue and would reduce damage to road infrastructure by heavy vehicles.

Regional and rural transport emissions need to be tackled through a wide range of Evs to suit business and farming needs, along with charging infrastructure.

Urban transport emissions need to be tackled by availability of work EVs – utes, vans – and sedan EVs, and also improving public transport and active transport infrastructure to encourage modal shift. Protected bike lane network can be done relatively quickly with fairly low expenditure. A Safe protected Cycling Network needs to focus on connecting schools, local shops, local railway stations. Make cycling and walking safe and convenient will rapidly increase patronage. This will also reduce congestion. Bikes also provide a cheap and equitable transport option, especially for those facing cost of living issues.

On Renewable Hydrogen use to decarbonise transport

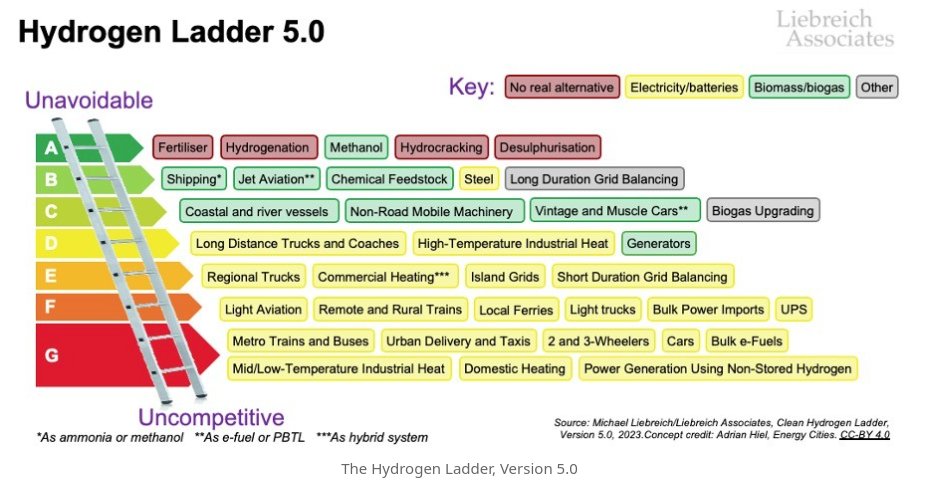

Hydrogen will have limited use in decarbonising transport. Perhaps its greatest potential will be in conversion to ammonia for use in shipping, however it may be used for hybrid aviation down the track, or in the production of e-fuels for jet aviation. For road transportation its use looks very niche and inefficient: perhaps some use as a fuel for long distance road freight in competition with truck battery systems being developed. It is a very inefficient use in hydrogen fuel cell electic vehicles (FCEV). Building an Australia-wide hydrogen refuelling station network and transporting hydrogen would be costly and very inefficient, and add to flammability accident risk on our roads. We should follow the Hydrogen Ladder for uses of green hydrogen to maximise decarbonisation effort. Many of the top priorities are industrial processes and fertilisers, but also including long duration grid balancing. See Michael Liebreich, October 21, 2023, Hydrogen Ladder Version 5.0, https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/hydrogen-ladder-version-50-michael-liebreich/

[…] Action Merribek contributed a submission in December on the Federal Government Transport and Infrastructure Net Zero Roadmap and Action […]

LikeLike